Six hours a day, five days a week from now until September is the rough schedule for dissertation work. While most of it has been spent making the most of opportunities outside the course, it's time to focus on what I came here to do. It's dissertation time.

![IMG_20150522_141634[1]](https://rosacarbo.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMG_20150522_1416341-1024x768.jpg)

![IMG_20150525_124053[1]](https://rosacarbo.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMG_20150525_1240531-1024x768.jpg)

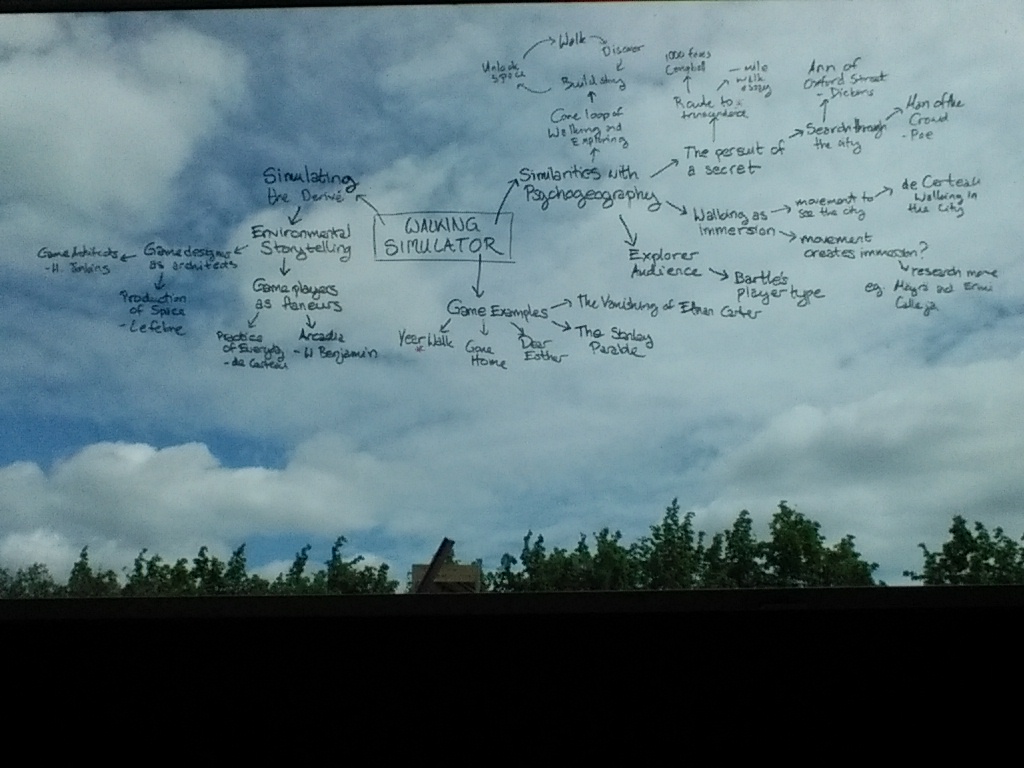

Days have been spent writing on windows, drawing clouds of thoughts that would combine into storms of ideas. I've been trying to find a string that would tie together the research I've been doing over the course of this academic year. This includes fields such as architecture, geography and games design, writers from Henri Lefebvre to Henry Jenkins, games like Gone Home or Year Walk, environmental storytelling, immersion, navigation, urban narratives and of course my sweetheart: psychogeography.

A little snippet of what I plan to do:

Walking is a practice that has gone beyond the mechanics of bodily movement. It is endowed in meaning, critical and aesthetic, environmental and personal. In 1790, Wordsworth and Jones began a 2000 mile journey through the European continent. The hypnotic rhythm of walking stunned them with fatigue and raised them to a plane of transcendence (Self, 2015). Walking to the early British psychogeographers was a route to spirituality in a disenchanted world. The nineteenth century flaneur, a leisurely observer of urban space, would end up immersing themselves into the intoxicating past of the city (Benjamin, 1939) similar to the ‘deambulation’ practices of Surrealists who would walk to reach a state of hypnosis (Basset, 2007). This immersion into the landscape allowed for the excavations of hidden secrets and exploration of spatial patterns. The exploration of landscapes was used politically by the Situationists International (Sadler, 1999) and as a window into an occult mysticism of the city by British psychogeographers (Coverley, 2010).

Like the Situationists International, geographers like Michel de Certeau (1988) use the immersion invoked in walking to read cities. Walking is a spatial trajectory that allows the exploration of hidden stories, embedded in the landscape. Early writings followed the spatial pursuit of a secret. In Edgar Allan Poe’s Man of the Crowd (1840), the writer followed the nightly wanderings of a man through London. Throughout the voyage, in which the author falls deeper into the hypnosis of insomnia and the rhythms of the walk, Poe takes a psychological anonyme. He abandons his identity so he can reattach himself to that of the vagabonding stranger and at the same time assume the position of Walter Benjamin’s archaeologist, collector and flaneur. In his alienated position, the flaneur can excavate the hidden secrets of nighttime London.

At the heart of the ‘derive’, or ‘drift’, is a ‘playful-constructive behaviour’ (Debord, 1958). Playful walking represented a fight against the boredom of the modernist city and the delusions of control (Chtcheglov, 1953). It aims to excite the body and the senses through the sudden changes in ambiance in an attitude of resistance against functionality. The practice is often considered an ‘elaborate game’ by geographers (Bassett, 2007: p.401). One that draws a player's attention to the stories of the environment.

The steam store has seen a sudden appropriation of the term “walking simulator” used on games such as Year Walk (Simogo, 2013), Gone Home (Fullbright, 2013), Dear Esther (The Chinese Room,2012), The Vanishing of Ethan Carter (The Astronauts, 2014), The Stanley Parable (Galactic Cafe, 2011) and Life is Strange (Dontnod, 2015). Even games from before the term was coined such as Myst (Cyan, 1993) have been tagged as a walking simulator. This projectis a literary analysis into the patterns of these games, arguing that at the core of their design is the psychogeographic derive.

This project will concentrate on Year Walk and Gone Home as two examples of walking simulators. Year Walk has been chosen for its critical acclaim (Unity, 2013; BAFTA, 2014) as well as its strong references to psychogeographic practices. Gone Home has been chosen for the writers extended experience with the game as well as its use as a point of reference for other walking simulators. It will identify the similarities between walking simulators and derives by comparing these two games, formally and aesthetically, to psychogeographic practices. Through the use of a gameplay log, it will identify the games goals and mechanics as well as their use of environmental storytelling and ludic experience.

It thus argues that an understanding of psychogeography, its practice and reading, can help create more immersive environmental storytelling games such as walking simulators.

I'm aiming to have the essay come in conjunction with a game demo. What the game is going to be is still a bit up in the clouds. To brainstorm I've been walking down the route of Valencian rondalles, les falles and various other local traditions. I think it's time I put my home city on my map of games.

![10447872_10152100277102035_1970005512417920652_n%255B1%255D[1]](https://rosacarbo.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/10447872_10152100277102035_1970005512417920652_n255B1255D1.jpg)

Published by: rosa in Uncategorized